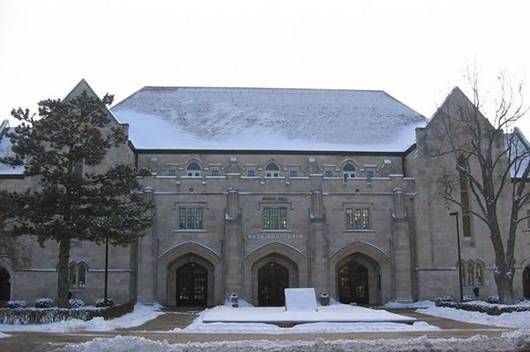

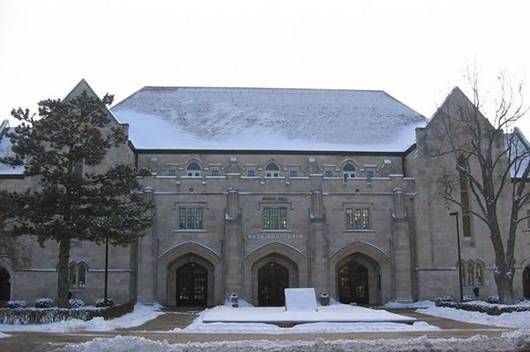

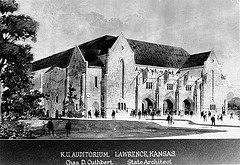

HOCH AUDITORIUM (1927 -1955)

Image: University Archives

Hoch Auditorium became home to Jayhawk basketball when the team abandoned old Robinson Gymnasium.

Growing Pains. Prior

to Allen Field House, the basketball Jayhawks had played in Hoch Auditorium. Not

only was this facility simply too small to accommodate an expanding student

body, but, as Allen once told a Kansas Senate committee, its basketball floor

“was laid on concrete” and lacked “resiliency,” causing his players to

suffer “sprains, bruises, and shin splints.”

|

June 15, 1991 By 1925, the University of Kansas was beginning to outgrow old Robinson Gymnasium, which had been built less than 20 years earlier. Due to rising enrollments and the popularity of KU basketball, overflow crowds were taxing the facility’s capacities, presenting a clear and present fire danger that University administrators could not long ignore. In 1927, KU secured upwards of $300,000 to erect Robinson’s larger (and presumably safer) replacement, Hoch Auditorium, which was named in honor of Edward W. Hoch, a former Kansas governor and regent as well as a long-time supporter of the University. Ironically, this very structure built to lessen, if not eliminate, the risk of fire, was consumed and ruined by a lightning-induced fire on June 15, 1991. It is a small wonder, though, that fiery disaster did not strike Hoch sooner. Nine months before its October 1927 dedication, the state’s fire inspector responded to inquiries about the building’s safety. Not to worry, he said, for although Hoch’s supporting arches were made of wood, the ceiling’s height profoundly diminished the risk that a floor fire would threaten the entire structure. That settled, three years later, fearing a heavy snowfall would collapse the roof, contractors reinforced it with additional heavy wooden beams – perfect kindling in the event of a fire. Over 60 years passed without serious incident, yet there were many Cassandras along the way, warning of impending doom. On November 15, 1974, for example, a front-page story in the University Daily Kansan announced, “Hoch Called a Fire Trap,” and cautioned that “the University of Kansas is faced with potential tragedy … if present smoking and fire prevention regulations aren’t more strictly enforced.” Although the principal concern revolved around students smoking cigarettes inside Hoch (which was officially prohibited), KU’s executive vice chancellor, Del Shankel, warned of potentially disastrous structural flaws. “The ceiling is highly flammable and the curtains are flammable,” he told the Kansan. “A fire could go through that whole roof in a hurry if one ever got started.” Mathematics professor Robert D. Adams concurred, wondering “why we schedule anything in Hoch, especially if it’s going to have a full house. The place is a tinderbox.” Compounding the dangers associated with flammable curtains and ceilings, Hoch’s designers had covered its interior with an acoustic-enhancing material called Celotex. The only problem, noted the Kansan, was that Celotex had been banned for use in construction in 1970, owing to its intense flammability. When asked about the safety of Hoch Auditorium, Harry M. Buchholz, director of the physical plant, admitted, “the problems arise mainly because of the structure of the building.” Yet he added, frankly, “It’s very old and would take considerable expense to get back in line with present standards.” Considering that the University of Kansas engaged in annual battles with State Legislature for money to erect much-needed new buildings, it is not surprising that the costly repair and refurbishment of an old one was not a high priority. During its 64-year history, as the Topeka Capital-Journal once noted, Hoch Auditorium was “a favorite target of lightning.” And according to an article in the March 1992 edition of Kansas Engineer, “When the KU Police Department offices were housed in the building, they would move their vehicles as storms rolled in to Lawrence. Lightning would often hit Hoch, causing roof material to slide off the roof and down onto the cars below.” Inconceivably, no one had ever thought it necessary to install rooftop lightning rods until mid-1991. Indeed, that very summer, plans called for the restoration of Hoch’s wood-shingled roof including the addition of lightning rods for the first time. But until the work began, Hoch lay prone and unprotected. It was easy prey for a 53,000-degree lightning bolt that split and seared its roof on June 15, 1991, just days before the start of the scheduled improvements. According to the Kansas Alumni magazine, “The fire started around 3:20 p.m., shortly after a violent thunderstorm began pelting the Lawrence area with heavy rain and pea-sized hail.” In its professional analysis of the disaster, Kansas Engineer told how fertile an environment Hoch Auditorium was for fire, how it was indeed “a tinderbox,” as Prof. Adams had so presciently described it 17 years earlier. “The void between the ceiling and the roof … provided nearly 550,000 cubic feet of air,” reported the magazine. “Over 58,000,000 BTU’s of heat were possible with the amount of wood and air present in the void. Add a channel of lightning that is capable of producing heat exceeding 53,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and you have fire.” Fortunately, the Lawrence Fire Department already had a fire engine on campus, responding to an alarm at Watson Library, so firefighters were able to reach Hoch within minutes. Yet most of the Department’s fire engines were on the city’s north side at the time, fighting a blaze that had broken out at the Packer Plastics plant. Nonetheless, the six firefighters on the scene did their best, gaining access to the auditorium and “flowing 200 gallons of water per minute through hand lines.” It was a noble effort, but they never had a chance. According to the Kansas Engineer, “the fire was at such a high temperature that the water was essentially evaporating before it reached the flames.” By 7 p.m., over 70 firefighters from Lawrence and such nearby cities as Lenexa, Overland Park, and Shawnee were finally able to contain the fire, but not before it had collapsed the roof, gutted the entire structure, and left little more than charred, smoking remains. “It was a total loss,” said KU police Lt. John Mullens. In a little under four hours, one of KU’s oldest and most revered buildings – one of six on campus listed in the National Register of Historic Places – was gone. Notwithstanding the estimated $13 million in material damage, the fire destroyed irreplaceable archival materials belonging to the University’s FM radio station, KANU, and displaced thousands of students and faculty scheduled to attend or teach fall semester classes in Hoch. The loss of the building itself, however, was what cut KU deepest. Older alumni remembered Hoch Auditorium as the home court of KU’s basketball teams from 1927 to 1955, before the Jayhawks moved over to Allen Field House. Others recalled that Hoch had hosted the annual Rock Chalk Revue for 40 years, and had provided a KU venue for some of the world’s most famous personalities and talented performers including John Philip Sousa, Sergey Rachmaninoff, Isaac Stern, John F. Kennedy, Count Basie, Steve Martin, Itzhak Rabin and former British prime minister Anthony Eden. On April 4, 1968, according to Kansas Alumni, comedian Bill Cosby was doing a show at Hoch, but “ended his routine early when he got news that Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot.” Indeed, KU Chancellor Gene A. Budig spoke for everyone when he said that, “Countless alumni and friends have memories of the historic old facility and the outstanding arts and athletic events held here. We have witnessed the passing of an old and dependable friend.” The State of Kansas, however, was not immediately helpful. On June 28, 1991, 13 days after the fire, the State Finance Council rejected KU’s application for $197,000 in disaster-aid relief. Owing to the intransigence of a single legislator, the Council could not release the money even after an 8 to 1 vote in favor, since any decision required a unanimous vote. University administrators lashed back, with vice-chancellor Shankel insisting that the state’s emergency fund “exists specifically for responding to ‘acts of God’ and unforeseeable emergencies such as the Hoch fire. This event,” he continued, “was certainly unforeseeable in the regular budget process … [and the work is] absolutely essential to protect public health and safety.” Kansas Governor Joan Finney was sympathetic. After touring the ruined auditorium, she described it as a “heartbreaking sight.” However, she added, “The situation in the state is very difficult. This is a year of reckoning, so we’ll have to see where the future takes us economically.” As for repairing or replacing Hoch Auditorium, “the answer at this time is there is no answer.” Finney’s non-committal comments led many KU people to fear that “the burned-out shell of Hoch would sit for years, casting a pall over the beautiful campus.” As it turned out, though, the Hoch ruins did not become a permanent

feature of Mount Oread. On May 22, 1992, an unexpected “federal

windfall” enabled Governor Finney and the State Legislature to enact

legislation that provided a total of $18 million over three years for

the complete rebuilding of Hoch Auditorium. By most contemporary

accounts, securing such a large sum would have been impossible without

the indefatigable efforts of Chancellor Budig. According to Kansas

Alumni, for months Budig “lobbied endlessly for funds, speaking in terms

of Hoch’s history and its importance to meeting the scholarly mission of

the University.” In honor of his work, the State Board of Regents named

the rebuilt structure Budig Hall, but retained “Hoch Auditoria” on the

façade and as the collective name for the building’s three new lecture

halls. One could not but be impressed by the building’s high-tech, “Star Wars” interior, as the Topeka Capital-Journal described it. The University’s assistant provost, Richard Givens, told the paper “KU is one of the only universities in the country to have a facility like Budig Hall. Other schools also use the latest technology, but not to KU’s extent.” Back in August, the Kansan had reported that “the first days of classes” in Budig “left students and faculty in awe.” But the building’s exterior was equally remarkable, particularly because the architects were able to preserve Hoch’s gothic, limestone façade while incorporating flying-buttress-like glass atria on the east and west sides. It was a pleasing fusion of disparate architectural styles. In his dedicatory address, Chancellor Hemenway described Budig Hall as “a modern day phoenix rising from the ashes” and went on the express the University’s appreciation for its namesake’s efforts. After serving as chancellor for 13 years, Gene Budig left KU in 1994 to become the commissioner of baseball’s American League. However, he happily returned to Lawrence to celebrate the opening of Budig Hall, bringing with him some of the sports world’s biggest names, including New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, Chicago Bulls and Chicago White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, and Kansas City Royals legend George Brett, among others. Yet, according to the Capital-Journal, “even with some of baseball’s most influential figures in town for the occasion, … Gene Budig was clearly the center of attention.” “My time here was some of the most productive of my life,” he said, “and this university is very special to me and the members of my family. I would do anything to support and help it. So I am extremely humbled by this entire experience.” There is no indication that Budig brought it up in his remarks, but

construction of the Hall had taken two years longer than originally

anticipated and had cost, not $18 million, but $23 million. As the

Capital-Journal reported, however, much of the delay and increased

expense could be traced back to the fact that, “fireproofing in the

ceiling wasn’t thick enough … and replacing it [had] set construction

back.” Given the building’s history, this extra last-minute effort was

probably time (and money) well spent. John H. McCool The views and interpretations expressed in this article are those of the author and may not necessarily reflect the official position of the University of Kansas. © 2004-2005 University of

Kansas Memorial Corporation |

Budig Hall is a major renovation of the building that originally opened as University Auditorium in 1927 and 11 years later was named Hoch Auditorium, after Edward W. Hoch, Kansas governor 1905 to 1909. Fire sparked by lightning destroyed Hoch Auditorium on June 15, 1991

The House of Horrors, 2/15/2008